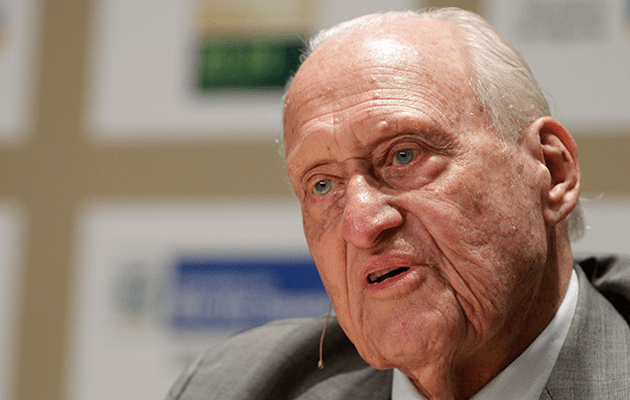

Joao Havelange, one of the most influential men in modern sport – if not the most influential – has died overnight in Rio de Janeiro aged 100.

Havelange, former president of world football federation FIFA, IOC member and Olympic swimmer and waterpolo player, had played a key role in helping bring the current Olympic Games to his home city.

At the Copenhagen Session of the International Olympic Committee in 2009, with Rio competing against Chicago, Madrid and Tokyo, Havelange invited the Olympic family “to join me on the beach of Copacabana to celebrate my 100th birthday at the first Olympic Games in South America.”

In fact, Havelange was 100 on May 8. A ever-more-controversial figure after revelations of his role in the ISL scandal, Havelange’s name was the original title of the Engenhao stadium which, temporarily re-baptised at the Estadio Olimpico, is the stage for the athletics events at Rio 2016.

Jean-Marie Faustin Goedefroid de Havelange swam for Brazil at the 1936 Berlin Olympics and, to pay his sea-crossing home, won a string of bare-knuckle boxing contests on the Hamburg dock-front. He returned to the Games, in London in 1948, in the tough discipline of waterpolo. Well into his late 90s he was still swimming in the pool of his home or hotel every morning before breakfast.

Havelange crushed one rival after another to build up a transport business and scrapped his way up the greasy pole of sporting power to become president of the old Brazilian sports confederation. He became a member of the IOC in 1963 and, though not a football man, used Brazil’s World Cup hat-trick in 1958, in 1962 and in 1970 as the platform to oust Sir Stanley Rous as FIFA president.

Englishman Rous did not see the danger. He did not understand the ambition for change and opportunity in Africa, as did Havelange; he did not see the need to bring China in from the cold, as did Havelange.

The evidence was there but Rous was betrayed by his own arrogance. Havelange made no secret of his aim long before their 1974 showdown. He had set his mind on it from a long way out, in 1970, while Brazil were still celebrating their World Cup treble. Havelange even told Rous, to his face, over lunch in London towards the end of 1971.

By then Havelange had gone public at the South American confederation congress. He had also assigned associates with well-honed sports and political contacts in the various continents both to spread the word and identify issues he could weave into an action programme.

Rous was vulnerable on a number of fronts. He was deaf to the clamour for greater recognition from Africa, he did not comprehend his folly in ignoring worldwide antagonism to South African apartheid; and his loyalty to nationalist China (Taiwan) blinded him to the political significance represented by the mainland (then out in the cold).

Years later, Havelange told biographer Ernesto Rodrigues: “I could see in Sir Stanley’s eyes that he never believed I was a threat to him.”

Neither, to be fair, did the Brazilian media.

Havelange delighted Africa by promising to expand both the World Cup finals – from 16 to 24 teams – and the FIFA executive committee. He also asserted that FIFA would pay, for the first time, all exco members’ travel and accommodation costs. He offered the Soviet Union his IOC support for a Moscow Olympics in exchange for a presidential vote.

If the Soviets – who also dictated the other east European votes – had any doubts these were resolved when Rous committed a blunder of crucial proportions. He expelled the Soviet team from the 1974 World Cup qualifiers for refusing to meet Chile, in a play-off, in Santiago’s Estadio Nacional which had been used as a prison camp in the CIA-backed overthrow of Marxist President Salvador Allende.

That sealed Soviet opposition (in an era when the USSR also wielded considerable influence in Africa).

Simultaneously Havelange was undertaking a punishing world tour spanning more than two years and which took him to Africa, Asia, Oceania, Europe and Central and North America. All this, remember, in the tiring turbo-prop days long before jet travel had become commonplace.

Havelange had no compunction about the leaders he met, whether monarchs or murderers. If they could deliver a vote, he reeled it in.

Freinds in high places…Havelange stands between U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, left, and Brazilian player Rivelino.

A high-up contact in Lufthansa offered the six free flights in his gift to the presidents of the minnow islands of Oceania for FIFA Congres in Frankfurt. Another went to FIFA’s office in Zurich and paid, in cash, the outstanding membership dues of 14 African nations; had the fees remained unpaid, they could not have voted.

Just before the presidential ballot, Rous and his western European supporters lost a vote on a Middle Eastern proposal, more theoretical than practical then, that FIFA should admit mainland China. This was a first signal that he was damaged goods.

Havelange, in his pre-ballot speculation, had discounted one third of his ‘promised’ votes on the basis that they would turn out to be lies. In the event he won the first ballot 62 to 58. It was not sufficient but it was enough to turn support his way decisively for the second vote in which a simple majority was enough: 62 to 52.

So began a 24-year reign which ended in Paris in 1998 when Havelange’s chief executive and general secretary, Sepp Blatter, defeated the favourite, UEFA president Lennart Johansson. Blatter had Havelange to thank. Before the vote Havelange had summoned many of his old allies and pointed out precisely how many millions their federations had received in FIFA grants during his presidency.

He had them eating out of his hand, almost literally.

Winning the FIFA presidency was just a start for Havelange. In Frankfurt, decisively, Horst Dassler had swung over to the Havelange camp. Dassler was scion of the adidas empire but was always far more interested in sports politics than sportswear.

Together with the English super-salesman Patrick Nally he put it effect a concept called, initially, Intersoccer Four. This computed the four best advertising placements around a football pitch and priced the package to sector-exclusive sponsors.

First they went to Coca-Cola and used the revenue to buy back the rights to all the various FIFA and World Cup images which had been virtually given away down the years.

This is the reason Coca-Cola enjoys a position of first among equals in the pantheon of FIFA sponsors.

Dassler then bought out Nally and, during the 1982 World Cup finals in Spain, created for the use of Havelange a marketing agency to control all FIFA’s commercial activities. The agency: International Sport and Leisure, commonly known as ISL.

Marrying sponsorship exclusivity with the sale of exclusive broadcast rights in a rapidly-exploding television world proved a gold-mine.

FIFA led, others followed. Havelange introduced ISL to other Latin sports powerbrokers: Juan Antonio Samaranch at the head of the International Olympic Committee and Primo Nebiolo of the IAAF which ran athletics, the value element at the Games.

When Havelange was elected president, FIFA had a staff of 11, all in Zurich; now it employs hundreds around the world; the World Cup now features twice as many teams, 32 compared with 16 and is ‘supported’ by a worldwide range of youth and women’s tournaments.

From a wider perspective, that TV/sponsor model which empowered Havelange and turned football into the most overwhelmingly dominant of sports has been copied by all the rest.

Havelange thus commanded unprecedented power of sporting patronage on behalf not only FIFA but in his own right. Everyone in the world game ‘owed’ him. While successor Blatter has been a prisoner of the need to keep voters onside, Havelange commanded them.

He wielded an iron fist in an iron glove.

An autocratic style and opaque political and commercial agenda were not to everyone’s liking. Even FIFA’s official centenary history delivers a highly-critical analysis of his dealings with the military dictatorship which ran Argentina at the time of the 1978 World Cup there.

Havelange maintained his own FIFA office in Rio and visited Zurich occasionally, relying on Blatter to run the Swiss show. But he was always The Boss.

On his first visit to Zurich after being elected FIFA president, he was furious to find no-one at the airport to greet him. Ever afterwards one member of the Zurich staff was always primed, at a moment’s notice, to drop whatever else was happening and leap into attention and action as Havelange’s personal chauffeur.

Unholy trinity…Football’s three Wise Monkeys…Sepp Blatter, Joao Havelange and Michel Platini

Defeat was not a word which featured in the Havelange lexicon. Loyalty was.

Hence he resented how the worldwide anti-smoking lobby forced FIFA to drop R J Reynolds as a World Cup sponsor; and he was outraged at what he considered the political perfidy of Europe in backing South Korea against his long-favoured Japan in the duel for 2002 World Cup host.

Havelange, having been ambushed at dinner on the eve of the executive committee vote, responded with the then unique compromise proposal of a co-hosted World Cup . . . between two nations whose historic relationship was anything but neighbourly. But co-hosting worked, albeit at unnecessarily enormous expense. Havelange took the credit.

By then he was four years into presidential retirement while remaining a senior figure in the IOC and as influential as he proved in Copenhagen, in October 1999.

But power, and its use, inspires envy and enmity. UEFA, suddenly enriched in the early 1990s through its own use of the sponsor/TV matrix to create the Champions League, began to flex rebellious muscles. Other marketing agencies sought to challenge ISL for the FIFA contract.

Predators believed they saw Havelange losing his grip when he barred Pele from participation at the World Cup finals draw in Las Vegas in late 1993. The reason? Pele was involved in a battle back home in Brazil over TV rights with a new member of the FIFA executive committee. That new member? Ricardo Teixeira, then Havelange’s son-in-law.

Joao Havelange, and former son-in-law, Ricardo Teixeira, flank Pele.

Pele was just about the only well-known soccer face in the United States and his absence from the rostrum angered and baffled organisers and officials. But Havelange, as he later told biographer Rodrigues, was merely maintaining his code of family loyalty. If that meant snubbing Pele in front of the world, well, tough.

Around this time Blatter – infiltrated into FIFA by Dassler in 1975, one year after Havelange’s initial election – began to entertain dreams of the presidency. A first tentative attempt to build a voting alliance in Europe was crushed ruthlessly by Havelange. Blatter kept his job, just, but at the price of having to sack his closest aides.

Havelange duly stepped aside in 1998, having pulled the necessary strings to ensure that Blatter, representing evolution, defeated UEFA president Lennart Johansson, representing revolution. Also, of course, Havelange was relying on Blatter protecting his legacy.

That would have been ideal had ISL not gone bust two years later. The subsequent court case, in the Swiss lakeside city of Zug, revealed how the company had committed commercial suicide in trying to broaden its activities and dilute its reliance on the FIFA contract.

ISL had offered illicit inducements to sports powerbrokers – not only in the football world – to try to maintain its contractual primacy ahead of rivals such as Mark McCormack’s IMG.

Football revenues due to FIFA were siphoned off, instead, into a range of other sports. When these lost money, ISL sought to cover its track with a public shares launch. That had to be cancelled when a black hole in the accounts was revealed; bankruptcy was the inevitable consequence.

The extent of ISL’s nefarious dealings might have remained undetected had the Swiss authorities not considered the collapse so significant as to prompt criminal proceedings. This was when the infamous ‘list’ of beneficiaries came to light.

Havelange is believed to have been among them (along with Teixeira, South American confederation president Nicolas Leoz, African president Issa Hayatou and IAAF president Lamine Diack). If and when the file will be opened to public inspection is a matter for the Swiss supreme court. Even so Havelange, last December, resigned his membership of the IOC rather than face an ethics panel inquisition.

He remained a lionised figure in Brazil . . . And his legacy is the world of sport as we know it.