Joel Richards on the reaction to Maradona’s death in Argentina

“There is only one Diego,” said Carlos Tevez, a week after Maradona died. “Diego is God.”

Tevez, one of the many Argentine players to have once been labelled “The Next Maradona”, had just scored Boca Juniors’ winning goal in the first leg of the Copa Libertadores tie with Brazil’s Internacional. The club captain controlled the ball in the area, swivelled and scored, and then as the team celebrated, lifted his No.10 shirt to reveal the shirt once worn by the number ten. El Diez.

It was the shirt that up until then Tevez had admired as it hung on the wall at his home. It is the one Maradona wore in the memorable 3-0 win over River Plate at the Bombonera in 1981. The grainy footage shows a virtually unplayable Maradona. Only the kicks and shoves of Daniel Passarella and Alberto Tarantini could stop him. Maradona capped that performance with one of his most iconic goals in Argentine football – receiving a cross inside the area, feinting, leaving 1978 World Cup winning goalkeeper Ubaldo Fillol on his knees, before passing the ball coolly into the net.

Tevez’s tribute in the days after Maradona’s death mirrored Lionel Messi’s – both raised their shirt after scoring to reveal one once worn by their idol. And both players sought a moment for themselves, away from their team-mates, for a private, intimate tribute. But the outpouring of grief in Argentina was, and still is, anything but private.

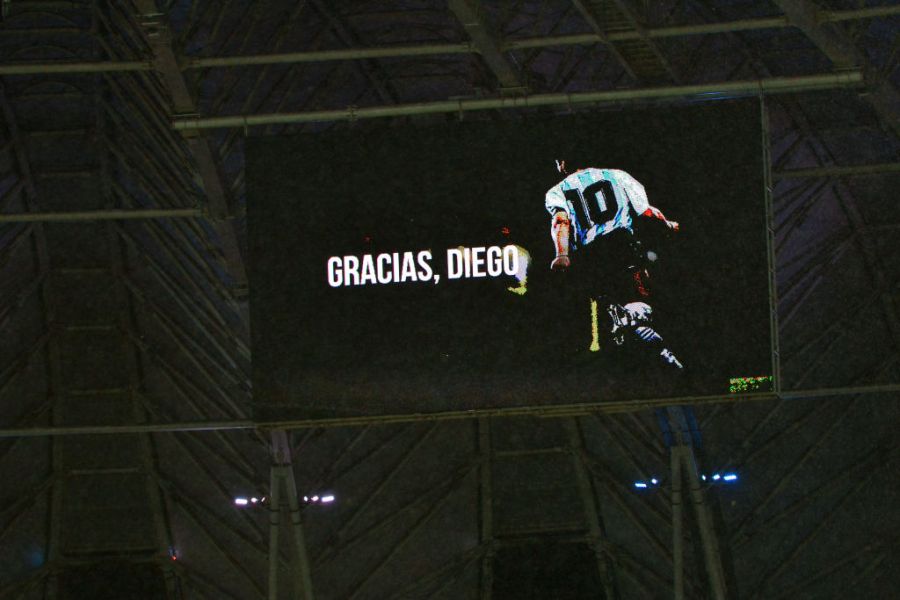

The Bombonera, where Maradona dazzled crowds in the 1980s and then years later would be seen in his private box at games, was just one of the places transformed into an altar after the news broke, people leaving flowers, pictures and messages. The government decreed three days mourning. “Diego will be one of those people who never dies,” said president Alberto Fernandez.

Authorities expected a million people at the wake, held at the Casa Rosada.

Between those who queued for hours under the hot Buenos Aires sun and those who lined the route of the funeral procession, it must have been more.

“There is great sadness,” said Marcelo, the artist painting a street mural of a young Maradona on the day of the wake, “but it is also a celebration.” There were chants about the English, there were songs in Italian, there were drums, fireworks, and there were tears. “Football has died,” said one man in his sixties.

Perhaps only for Maradona does such hyperbole fit. There to say goodbye to Maradona were people of all ages, people of all backgrounds. Maradona was a footballer, a global superstar who led Argentina to win the World Cup. And then he transformed into something much larger, much greater. Amid the controversies, the excess, the addiction, was the rebellious and roguish cultural icon. He had Che Guevara and Fidel Castro tattoos, but countless people sport Maradona tattoos.

The poster for one of the many documentaries about El Diez illustrates his many incarnations. Amando Maradona, (Loving Maradona, a play on his middle name) features a classic team photo taken seconds before kick-off. The 11 players are all Maradona at different stages of his life – from the innocent youngster whose dream was to play in a World Cup, through the 1986 and 1990 captain, to the died hair, the ballooning stomach, and then the slimmed down version of Maradona who hosted his own TV programme La Noche del Diez some years ago.

In his final job in football, Maradona took charge of Gimnasia for 21 games, spending the last year of his life receiving a hero’s welcome in stadiums all around the country. His final away match as coach, fittingly, was against Boca in the Bombonera.

“What do I care what Maradona did with his life,” reads the quote attributed to the late Argentine cartoonist and writer Roberto Fontanarrosa, and which points to how many people here feel about El Diego. “I care about what he did for mine.”

Maradona meant so many things to different people in Argentina and around the world, so the reports of his depression and loneliness in his final days make for sad reading. In his final public appearance as Gimnasia coach he had barely been able to walk without help. Those close to him have said he simply no longer felt like Maradona.

As this went to print, just over a week after Diego Maradona’s death, 1986 World Cup-winning coach Carlos Bilardo had still not been told of Maradona’s passing. Bilardo, now aged 82, is suffering poor health and his family was shielding him from the news. A group of ex-players including centre-back Oscar Ruggeri were expected to tell Bilardo, who considered Maradona “the son I never had.”

Article by Joel Richards

This article first appeared in the January Edition of World Soccer. You can purchase old issues of the magazine by clicking here.