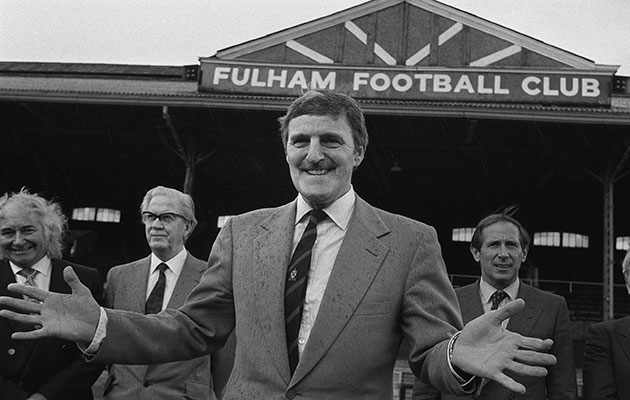

So many memories of Jimmy Hill, whose death has prompted many an encomium.

Though in his latter years, before he was besieged by Alzheimer’s, the bleak fact is that he became something of a figure of fun. Not least to the football world at large.

This was grotesquely unfair, because British players owed him such a massive debt. He of course it was, as Chairman of the Professional Footballers’ Association, previously known as the Players’ Union who, well abetted by its competent secretary, Cliff Lloyd, won the bitter battle against the League, as represented by dour isolationist Secretary Alan Hardaker, and Chairman Joe Richards, to abolish the infamous maximum wage which then stood at £20 per week.

£20 then would amount to a substantially greater amount today, but would still be derisory. In fact the top wage when the 1914 war broke out was £9 a week and in 1919, the war over, it was reduced by the League to £8. Which it still was when war began again in 1939.

After covering the Rome Olympic Games in 1960 the Sunday Times gave me its first ever sports column and I promptly used it to back Jimmy Hill in his fight against the maximum wage. A major satisfaction came when the paper, basically a conservative one, actually published a leader article, nothing to do with me, exhorting the players to strike!

Jimmy loathed his confrontations with the obdurate Hardaker and Richards but the battle was well and truly won and Jimmy’s own Fulham club mate Johnny Haynes became the first £100 a week English footballer. A surprise was that Jimmy had no help from the most eloquent British footballer of his time, Danny Blanchflower, captain of Spurs and Northern Ireland.

A personal memory of Jimmy takes me back to the Slough Greyhound Stadium in the early 1960s when the little Sunday team I ran for a long time, Chelsea Casuals, were playing the so-called TV All Stars, including an ageing Malcolm Allison and Ken Tucker ex-West Ham.

The organisers, much under estimating us – we had a number of accomplished players, not least Mike Pinner, amateur keeper for Aston Villa and Sheffield Wednesday, who’d play for us out of goal. Since it was insisted that the ex-Fulham and England centre half, Jim Taylor would quite superfluously play for us, that meant Mike had to go into goal and our defence was consequently impregnable.

Soon after half-time, Jimmy awarded the TV Stars a fictitious penalty, but we were still leading 3-1 late in the game when he took off his referee’s jacket, played for them, scored twice, and the game ended at 3-3!

The son of a failed bookmaker, he turned professional as a left half with Brentford and distressed them when he quit them for Fulham, becoming a functional inside right, renowned for his beard; a rarity among players then.

On retirement, a gifted coach, he excelled as manager of Coventry City, taking them from the Third Division to the First, where they would long remain, though he left them when they refused him a 10-year rather than a five-year contract.

After Coventry he was responsible for a successful profusion of innovations, including the rise from two points to three for a League victory. Entering the world of television, he became for many years a greatly successful if somewhat controversial presenter and when he returned to Fulham as Chairman, he saved them from amalgamation with QPR.

When he was at Coventry with his infinite ideas, I remember writing a song about him to the tune of The Mexican Hat Dance; one verse went:

He’s the best. He’s depressed

He’s so cross with the Press saying no and not yet when the game’s in a mess.

They’re a pest.

But with such a galaxy of ideas, they couldn’t all be winners.

Chelsea’s 3-1 win over Sunderland the manner of it demonstrated that the team was glad to be rid of Jose Mourinho and released, rather than having deliberately malfunctioned under his aegis. Mourinho is beyond doubt one of the outstanding managers of any era, but it was all too plain that his methods had alienated his team.

I also believe the watershed may well have been his appalling behaviour towards the club doctor the Gibraltarian Eva Carneiro, who – has not been sufficiently emphasised in recent days – had no alternative but to go on the field to treat the prone Eden Hazard when the referee called her.

The FA disciplinary committee let him off far too lightly, appointing a presumed expert who declared that he had shouted not “ja di puta“, daughter of a whore, in Portuguese, but “hijo di puta“, son of a whore.

Now why would he do that?