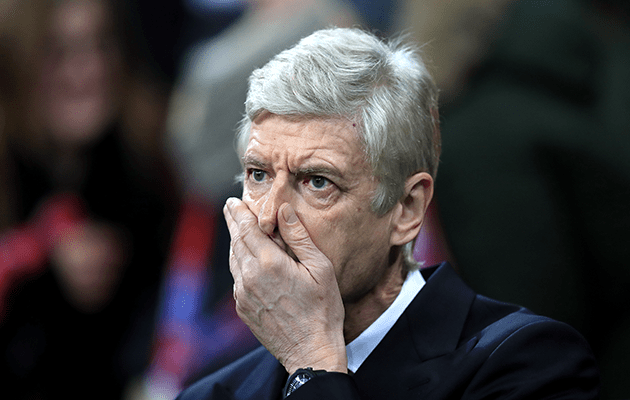

After that dreadful thrashing by Bayern Munich, Arsene Wenger’s days at the Gunners must surely be numbered.

Disaster was avoided at Sutton, but in Munich it became clearer than ever that Arsene had lost the plot. Indeed, for my part, I felt he should have gone a couple of seasons ago, when dreadful defeats by Chelsea, Manchester United, and Liverpool would have doomed any manager of a good Italian club.

Mesut Ozil’s loquacious agent, Dr Erkut Sogut, has defended his man’s bleak performance in Munich, pointing out that he had scant support from those around him. But the fact is that for some time Ozil has tended to disappear in the games when pressure is at its highest. He seems to have become what might be loosely termed a rabbit killer, and the fact that he has not yet signed an extension to his current hugely rewarding contract should scarcely preoccupy the club. By sharp contrast with the fact that the remarkable Alexis Sanchez is also holding out at the moment.

In parenthesis, you wonder just how much help Wenger gets from his assistant manager, Steve Bould, previously the defensive coach and before that a doughty centre back in a highly successful team.

The club’s board of directors like their American billionaire chief shareholder, Stan Kroenke, are hardly likely to contest Wenger. Indeed, sir Chips Keswick, the head of the board, has been known to stifle criticism at a shareholders meeting.

One frequently reads Wenger being extolled as the greatest manager in the Gunners history, but I would question that. That he has stayed in charge for a remarkable 21 years is beyond doubt or appreciation. But the greatest manager in the club’s history? As one who has written the official history of the club I would strongly question that claim and suggest that the accolade should be bestowed on Herbert Chapman.

Herbert Chapman, Arsenal’s greatest ever manager, led the club to multiple titles.

Under the remarkable Yorkshireman, the Gunners were transformed from a struggling club with no real right to be in the first division into the most powerful team in the land. They had no right to be promoted from Division 2 in 1919 when football resumed officially after the Great War, having come on 5th in the last Division 2 league. Some dubious work at the crossroads between bulldozing millionaire Sir Henry Norris and the Football League chairman resulted in the Gunners being promoted while and enraged Tottenham, already infuriated by the Gunners relocation to north London, going down to Division 2. On the bizarre grounds that Arsenal, though 5th placed, had been in the league longer than Spurs.

Chapman promptly bought the formidable inside-right Charlie Buchan back to the Gunners from Sunderland on a £100 a goal transfer. He would score 19. Beaten 7-0 on the opening day of the 1935-36 season, when the offside law had just been changed, Buchan proposed the Third Back Game with the centre-half moved back between the two full-backs. It instantly worked and the Gunners were away.

Chapman had won the last two consecutive titles with Huddersfield Town but had long wanted to come to London. He two major future stars in left-back Eddie Hapgood from non-league Kettering and 17-year-old Cliff Bastin from Exeter City, whom Chapman had to pursue into the family kitchen.

Bastin, turned by Chapman into a left-winger, would score 33 goals in a season. There were all sorts of major and minor innovations. White sleeves to go with the red jersey. A floodlit game. The renaming of the local tube station to Arsenal. Major stars such as David Jack and Alex James transformed into the fulcrum of the attack were expensively acquired. Chapman had an almost hypnotic power of convincing his players. He decided to turn young George Male from a modest left half into a top right back. By the time he had left Chapman’s office, Male was convinced he would become the best right back in the world.

Tom Whittaker returned from an FA Australian tour with a broken leg. Chapman told him he would make him the finest trainer in football and he did. Whittaker’s healing powers became an essential feature of success. Years later he would become the manager.