On the very day that the Brazil national team took a giant step forward, the country’s domestic game moved in the opposite direction.

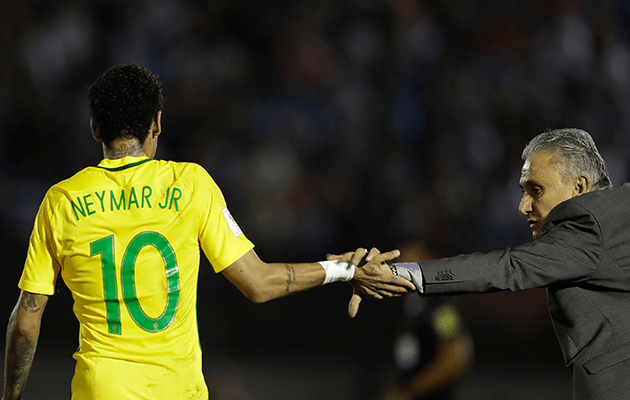

Last Thursday Tite’s men closed in on World Cup qualification with a seventh consecutive victory – and this one, coming from behind to win 4-1 away to Uruguay, was the most impressive of the lot.

Earlier the same day a General Assembly of the CBF, the country’s FA, made a Machiavellian option to keep club football in the dark ages.

One of the biggest problems of Brazilian football is its political structure. The country is divided into 27 states. Each state has a football federation, and the balance of power inside the CBF lies with these federations.

At one time, given the fact of a country the size of a continent, such an arrangement made some sort of sense. It has long since ceased to make any sense at all. The driving factors in the local game, the indispensable element in the mix, are the big clubs, who can count their supporters – or at least potential supporters – in millions.

But they are politically subservient to the federations, who base their power on the numerous tiny clubs within their domain. The federations have, in practise, turned into a tropical equivalent of the rotten boroughs of nineteenth century British politics, wielding power but representing no one and nothing beyond their own interests.

This is the overwhelming reason behind the continued existence of the State Championships, which clog up the calendar every year between January and May. These create problems for the big clubs – nowhere else in the world do traditional giants spend so long playing against tiny teams on a league basis, which obviously means they are operating well below their economic potential. And, in truth, the arrangement hardly benefits the small clubs, most of whom have a competitive calendar limited to three months a year.

But it is an arrangement which suits the federations, who take a cut from both ticket sales (mostly paltry) and TV rights (much more attractive).

The whole structure is clearly archaic, and so government legislation stepped in to change things. A law was passed with the aim of improving management of the football industry. One of the most significant changes made was the increase in the number of clubs allowed to vote in CBF elections. With 27 Federations and 20 first division clubs, the deck was clearly stacked in favour of the former. So the 20 second division clubs were also given a vote, leaving the Federations outnumbered – until last Thursday.

At the last CBF General Assembly before the changes came into effect, the powers that be announced a weighting system. The vote of each federation would be worth three, while the first division clubs would have two votes and the second division clubs one vote each.

The mathematics used to work 27-20 in favour of the federations. It is now 81-60.

CBF General Secretary Walter Feldman hailed the wisdom of the move, pointing out that it retained the same proportionality between federations and clubs – brazenly overlooking the undeniable fact that the whole intention of the new legislation was to alter this proportion in favour of the clubs.

Federal Deputy Otavio Leite, who drew up the law, complained that “the spirit of the law is being frontally offended,” while highly respected Atletico Paranaense coach Paulo Autori said that “they have given more power to the federations and they talk of democracy? They think we’re idiots.”

In a further move to lock in the current power structure, in order to stand for election for CBF president, a candidate needs the support of eight federations as well as five clubs. There is, then, no possibility of a genuine opposition candidate emerging.

Brazil’s sports daily ‘Lance!’ slammed the General Assembly as “a farce and another defeat for those who fight for the honesty, transparency and professionalization of our football.” The key, as it has been all along, is how the clubs will react. Santos president Modesto Roma was forthright. “I don’t like it,” he said. “I think the clubs have been betrayed. We had 40 votes and the federations had 27. Now in a sleight of hand it’s 81 against 60.”

But if the clubs really put it to the test, those 81 votes have little genuine power behind them. They could not stop the clubs breaking away from the structure of the CBF and organising their own league, with a rational calendar. But this degree of co-operation has so far proved well beyond the capabilities of Brazilian club presidents. And so while Tite and company march forward, the club game continues in reverse.