Frequently viewed through the prism of his alleged arrogance, rudeness and repeated clashes with the press and Dutch icon Johan Cruyff, Van Gaal would never pass a popularity test. But even his most obtuse critics would have to admit his strengths as a top-level coach: the intense commitment to excellence, his analytical ability, a relentless drive to win, his teaching ability on the training ground and a flair for sorting the wheat from the chaff in a squad.

At every club side he has previously taken charge of – Ajax, Barcelona, AZ and Bayern Munich – success has ensued; and however dysfunctional Manchester United were last term under the hapless David Moyes – dubbed “the Chosen One” by United fans after he succeeded Alex Ferguson last summer – who would bet against the Amsterdam native promptly repairing the Old Trafford damage?

Outstanding work

On guiding unfashionable AZ to the Dutch title in 2009 Van Gaal declared “I am

the best” – and the facts bear him out. Domestic championships in Holland, Spain and Germany; his outstanding work with Holland’s national team at this summer’s World Cup; and, last but by no means least, the wonderful Ajax dynasty he created in his first spell at the helm.

Having been an influential assistant coach at AZ and Ajax – serving under Spitz Kohn and Leo Beenhakker atthe latter – Van Gaal took full control of the Amsterdam club in 1991 when Beenhakker left for Real Madrid. And for the next half-dozen years the achievements just kept coming: the UEFA Cup in 1992, three straight Eredivisie titles (1994, 1995 and 1996), the 1995 Champions League – when Ajax beat Milan in the Final in Vienna – and Intercontinental Cup, plus a Champions League runners-up spot after losing on penalties to Juventus the following year.

The Ajax team that conquered Europe in the 1994-95 season is considered one of the finest club sides in the history of the modern game, and as the architect of that sleek and intelligent winning machine Van Gaal fully deserves to join the ranks of the managerial immortals.

There was so much to admire in a team that had an average age of 23 – the speed and precision of their passing; the way they dominated possession; their almost telepathic understanding; their intelligence and technical qualities; the way they maintained numerical superiority in all areas of the pitch; the players’ near-perfect drilling.

Using a fluid and flexible 4-3-3 formation featuring veteran centre-back Frank Rijkaard in the pulpit and a host of brilliant young guns – notably Clarence Seedorf, Edgar Davids, Jari Litmanen, the De Boer twins and Marc Overmars – the Ajax class of 1994-95 were a sight to behold, earning praise from deep football thinkers all over the world.

Current Bayern Munich boss, Pep Guardiola – who played under Van Gaal at Barcelona from 1997 to 2000 – does not hesitate to name that team as one of his all-time favourites, saying “In my eyes, they did everything a football team should do perfectly”, while ex-Real Madrid coach Jorge Valdano simply could not contain himself after losing to Van Gaal’s side in the 1995-96 Champions League group stage. The former Real and Argentina forward enthused: “Ajax are not only the team of the Nineties, they are approaching football utopia.

“Their concept of the game is exquisite, yet they have a physical superiority as well. They are ‘Beauty and the Beast’.

Soulless and sterile

It is a pity that so many in Holland do not share the same reverence for LVG and his methods as the likes of Guardiola and Valdano. For a large sub-section of the Dutch football commentariat, Van Gaal’s “system” with that Ajax side was soulless and sterile. Too much script, too much operating manual and far too little individualism and spontaneity.

And the critics may have had a point. The only way ahead with Van Gaal’s Ajax was to get with the programme and stick religiously to the coach’s highly mechanised version of the “Beautiful Game”. This meant possession, possession and possession; the team moving in set patterns; disdain for dribbling; the immediate switching of play from one flank to another when a “roadblock” developed; and a ban on wide midfielders overlapping the wingers.

“In Holland we are system mad and the world doesn’t know it,” complained ex-Ajax centre-forward turned media pundit Jan Mulder in David Winner’s award-winning examination of Dutch football, Brilliant Orange. “The world thinks we always play attacking football. But we play with the handbrake on.

“All this passing at the back…tick-tock, backwards, sideways, tick-tock…it’s boring. Too much fear, too much caution.

“They [Ajax] won everything they could win, but the football of Van Gaal in those years was dull football. Dull! I like Van Gaal personally but not as a coach. He got results at Ajax but they didn’t play as well as one thinks. They outplayed opponents, but it had no soul.

“Van Gaal is a teacher but doesn’t give his players much freedom.”

In the world of Van Gaal, the collective is paramount and there is no room for passengers or prima donnas; just 11 footballers who each perform specific tasks and work together in the most synchronized of fashions.

“Football is a team sport and members of the team are therefore dependent on each other,” he explained in The Coaching Philosophies of Louis Van Gaal and the Ajax Coaches by Henny Kormelink and Tjeu Seeverens. “If certain players do not carry out their tasks properly on the pitch, then their colleagues will suffer.

“This means that every player has to carry out his basic tasks to the best of his ability and this requires a disciplined approach on the pitch.”

Discipline on and off the field, always has formed the basis of the Van Gaal creed and woe betide any player who, willingly or subconsciously, does not come up to scratch in the behaviour and attitude department. Only two rules apply: you do not write on the walls, and you obey all the rules – especially those regarding punctuality, being ready for a training session half-hour before its start time, keeping personal effects neat and tidy, always displaying high levels of intensity and concentration in practice, sitting down to eat together and not reading a paper while doing so, and eating and drinking healthily.

Rolled down socks and untucked shirts were no-no fashion statements when he was in charge at Ajax – “You stand out from other players through your performance” – and at Bayern he spectacularly went to war with Luca Toni for daring to slouch in his seat in the club cafeteria.

“He always wanted the players to remain seated until everyone had finished breakfast,” Toni told Sport Bild three years ago. “But Italians only drink coffee for breakfast, so I finished early and made myself comfortable. All of a sudden, the coach appeared behind me, started screaming and pulled me up. He told me he was in charge and I should leave if I didn’t like it.

“I had never experienced someone like him before. I remember how he once tried to make it clear that he wasn’t afraid to drop the so-called big names. He just dropped his trousers to show us he had the balls to do it. He’s a crazy coach who doesn’t know how to treat his players.

“Guys like Felix Magath and him are coaches from another generation and can’t deal with the way players behave these days. Modern players want to communicate with their coach but that’s not possible with Van Gaal. Everything goes the way he wants it to go.”

Authoritarian figure

Whenever he is accused of playing the “great dictator”, Van Gaal always forcefully refutes the charge, insisting that his form of management has plenty of collaborative input.

“The media frequently portray me as an authoritarian figure, who thinks he knows it all,” he says. “But the people who work with me daily know better.

“I learn something new every day from the people around me. I ask everyone to say what he feels. I talk to the players every day. It is then my task, as the leader of that team, to make a selection from all the information available and to decide on the course to be taken. But then I expect everyone to support this course in public. To do otherwise is asking for problems.”

For all the supposed lines of communication, his reputation remains that of the autocrat who regularly butts heads with star names. He and French attacking maverick Franck Ribery were at daggers drawn throughout his tenure at Bayern Munich, from 2009 to 2011, and anyone attending Barcelona training sessions during the Dutchman’s first spell at the Camp Nou, from 1997 to 2000, would have been astounded at the ferocious tongue-lashings he aimed at Brazilian superstar Rivaldo, who was the European Footballer of the Year.

Angling for a switch from the left side of attack to a central playmaking role, Rivaldo must have fancied his chances of forcing the coach’s hand. But he had miscalculated and was instantly thrown off the team. The Brazilian had assumed he was the lead wolf; Van Gaal thought otherwise.

“Yesterday Rivaldo spoke to me and said he no longer wanted to play on the left,” Van Gaal told the Catalan media. “Because of that he’s been left out of the squad. It was a surprise for me and

a surprise for his team-mates.

“It’s a great shame. Barcelona has always had the philosophy that the club comes ahead of everyone – the players, the coach and all the employees.”

There is absolutely no possibility of player power in the Van Gaal kingdom. He does not massage egos or dispense special favours, and as long as he can have hi first XI on-message, plus a few others, he is happy to leave the non-believers behind, even to the point of making their lives hell.

“Barcelona was the worst experience of my life,” recalls French striker Christophe Dugarry, who in the 1997-98 season was unable to convince the Dutchman. “Van Gaal was foul and pedantic. Whether I was good or bad, he moaned. I used to leave training with tears in my eyes. To play football has to be a pleasure. But there it was a nightmare.”

Playing support

But if Van Gaal really is a monster, an autocrat and an implacable taskmaster all rolled into one – and one that exclusively rules by fear – players would be too uptight to perform. And for all the bust-ups, there are countless instances of pros totally buying into his message.

Ajax’s golden generation of Patrick Kluivert, Litmanen, the De Boer twins and Michael Reiziger all willingly rejoined him at Barcelona, and tempted to resign thanks to AZ’s poor results in the 2008-09 campaign he was talked out of it by the playing squad, with the volte-face paving the way for a closing of the ranks and the conquest of the Dutch league title 14 months later.

All manner of myths surround Van Gaal and one of the most persistent is that he is dogmatically wedded to 4-3-3. Yet fitting the system to the players, rather than vice-versa, he used a 2-3-2-3 at Barcelona, went with a counter-attacking 4-4-2 when AZ won the Eredivisie, and successfully implemented a 3-4-1-2 to thrash holders Spain 5-1 at this summer’s World Cup.

Along with all the silverware and a place in history as a tactical visionary, Van Gaal’s other claim to fame is his excellent record as a promoter of young talent. Any kid he considers to be made of the right stuff is invariably fast-tracked into the first team and over the years such bravery has reaped a rare harvest of brilliance at Ajax and kick-started the careers of Xavi, Andres Iniesta and Victor Valdes at Barcelona, and Thomas Muller and Holger Badstuber at Bayern.

It’s widely thought that Van Gaal’s preference for working with young players stems from their malleability, their openness to new ideas. But it might just be a product of his past, his work at the Ajax prodigy factory and the dozen years he spent in the real world as a teacher.

For a large portion of his playing career – which took him to Ajax, Royal Antwerp, Telstar, Sparta and AZ – he doubled up as a physical education master at the Don Bosco School in Amsterdam.

Displaying the drive and energy which has characterised his coaching odyssey, his daily regime in those days was definitely not for the faint-hearted.

Rising at the crack of dawn, he would take classes in Amsterdam, many of them with children with learning difficulties, then jump back in his car to drive long distance to football training. Typical Van Gaal: workaholic; totally committed.

With a nod and a wink towards the high-profile destiny which awaited him, Van Gaal’s time as thoughtful and technically gifted midfield general was littered with signs of leadership ability. Even as a 19-year-old with Belgian outfit Royal Antwerp he would point out team weaknesses to coach Guy Thys.

As captain of Sparta he constantly irritated irrepressible Welsh boss Barry Hughes with a constant stream of “advice” and served as a highly effective head of the Dutch players union.

“Too many people have the wrong impression of him,” says ex-Belgium, Club Brugge and Cologne striker Roger Van Gool, who played alongside him at Antwerp. “Of course, some will not like him, but he has a good character. He wants to help people. He can listen.”

Constant clashes

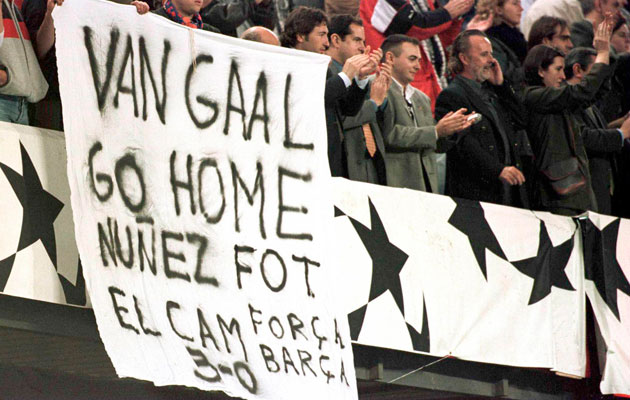

Needless to say, Van Gaal’s single-mindedness can cause him difficulties. Despite masterminding two La Liga titles in his first two seasons at Barcelona, his power base was whittled away by constant clashes with the local media over his reliance on Dutch personnel – eight players from the low lands proving far too many in the bastion of Catalan identity – and in May 2000 he was gone, uttering the immortal adieu: “Friends of the press, I am leaving. Congratulations.”

His reign at Bayern was the same story of romance, betrothal and a quickie divorce; elevated to cult hero after steering the Bavarians to a domestic double and Champions League silver in his first campaign, but then swiftly losing his grip in the second and becoming increasingly isolated as players and club hierarchy tired of his “I know best” routine.

Still going strong at the age of 62, Van Gaal is a man who will not be knocked down. Yes, he has had his share of personal and professional setbacks, not least the death of his first wife, Fernanda, to cancer in 1994 and his rejection as a youngster at Ajax. Then there was the six-month disaster of his second tour of duty in the Barca hot seat and his failure to take Holland to the 2002 World Cup.

But new challenges and new frontiers have always been his lifeblood, and after picking himself up and dusting himself off he simply goes again.

The competitive fires burn as brightly as ever. Next stop: Old Trafford.

This article appears in the July 2014 issue of World Soccer.